In my last blog post, I talked about the phenomenal rise and opportunities in Vietnam, but there are also challenges ahead. Some thoughts from discussions while there…

While the streets of Hanoi and Saigon (as locals still call Ho Chi Minh City) are vibrant, they also testify to the growing pains of this rapidly emerging nation, which only started international reintegration in 1986 after prolonged military engagement. In 1975, when the country reunified under a communist government, it was isolated and devastated from military action. Even today, younger generations of Vietnamese entrepreneurs talk from personal experience about how they and their families suffered during this period and the disastrous post-war collectivization of farms and factories which led to massive inflation and economic collapse. The shift in leadership and policies in 1985 heralded a new start for the nation, with free market reforms – known as Đổi Mới (Renovation) – starting the transition from a planned economy towards a socialist-oriented market economy. Private ownership, economic deregulation, foreign investment and newly resumed trade links with the world restarted the engine of growth.

While this turnaround – in a period of just 25 years – has been astoundingly successful, Vietnam still faces growing pains which will influence its future success. First, the balance between state control and free market forces – theoretically communism and capitalism are poor bedfellows, but the hybrid model has worked well for Vietnam so far. The question is whether it will for the future, and how it may need to evolve. Today, the government controls critical aspects of business, from import and export licences to suppliers of critical services such as telecommunications and finance. Corruption is a major issue and government relationships determine the success or failure of many enterprises. In many ways, business here is like the Wild West. One story we heard was of a major developer having finance withdrawn by a state bank – leaving a major project in doubt, without overseas funding. Nonetheless, finance is flowing into the economy fast from less risk-averse sources of capital, often from funds and entrepreneurs in other rapidly developing nations such as Russia and China. At some point, the hybrid solution of state control and capitalism will need to evolve to support a maturing economic environment – how remains a significant question.

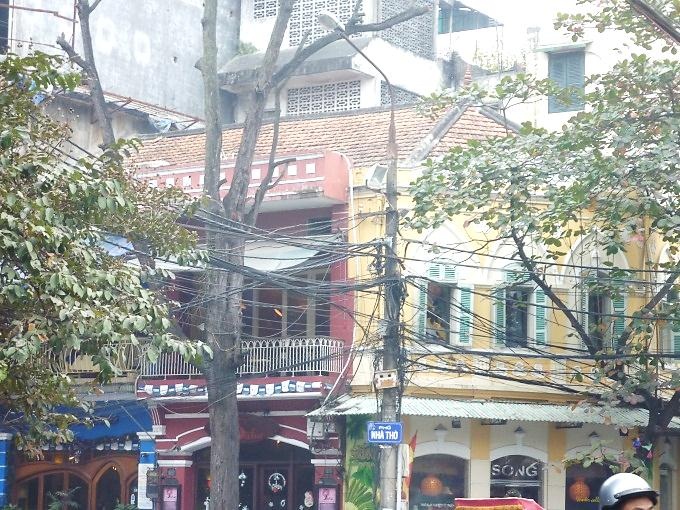

Infrastructure is also a significant challenge, particularly compared to competing nations such as China and South Korea. In a country with 2000 km between its major industrial hubs, a single track, poorly maintained road for much of the distance, plus poor rail infrastructure, means flying is the most efficient way to connect. Driving at speeds limited to 40 to 60 km over this distance takes 48 hours, impacting the movement of goods and people – including the growing influx of tourists. And driving in Vietnam is dangerous. Estimates suggest that 30 people a day die on its roads, which will be no surprise to anyone who has tried to negotiate its streets inside or outside the cities. The predominant means of transport for people and goods is scooters and motorbikes, with almost 19 million crowding the roads in 2006 according to the World Bank and the market has been growing some 20% per annum since then. As car ownership grows along with wealth, the daily mayhem of moving around becomes even more challenging. Added to the transport infrastructure challenges, are the urgent needs to upgrade telecommunications and electricity infrastructure – internet speeds remain low in even new housing and business areas, while electricity outages are frequent – and to provide adequate housing for a rapidly urbanizing population.

That’s not to say nothing is happening – infrastructure projects are evident everywhere – the Saigon and Hanoi skylines are being reshaped daily by skyscrapers and new roads taking shape. In fact, you will not recognize these cities in just a few years. The biggest issue is that building infrastructure takes time and money – and government involvement. Land ownership is another challenge – the government holds all land in trust for its people so land is leased – one reason that you will not see McDonald’s or Apple Stores in Vietnam, as these companies want to own land outright. 50 year property leases (residential or commercial) are subject to renegotiation at the end of the period, offering another level of uncertainty for individuals and businesses alike.

For these people and entities, hungry for growth and personal development, a further issue is the growing level of income inequality. The Porsches, Lamborghinis and designer stores on the main streets of Hanoi and Saigon and the skyscrapers coexist uneasily alongside ramshackle buildings with limited electricity and running water, home to those still facing the deprivations of poverty. How the government and society manage the growing gap between the haves and have nots, particularly as economic growth is expected to dip in the near term while inflation is rising, will be a key factor shaping the future development of the country. At best, the growth trajectory which is expected by the business people we spoke with to resume in 2013, will continue to pull living standards up for all. At worst, particularly if prices of basic needs (food, water, shelter) increase, there may be some social unrest.

The bottom line as I see it: The challenges for continued growth are significant for this amazingly successful country, but the desire is extremely strong to overcome them. Vietnam will likely continue to be a case study in evolving new models of governance and capitalism from which the rest of the world can learn. Keep watching…