Too often executives have viewed corporate social responsibility (CSR) as just another source of pressure or passing fad. But as customers, employees, suppliers—and indeed, society more broadly—place increasing importance on CSR, some leaders have started to look at it as a creative opportunity to fundamentally strengthen their businesses while contributing to society at the same time. They view CSR as central to their overall strategies, helping them to creatively address key business issues.

The big challenge for executives is developing an approach that can truly deliver on these lofty ambitions—and, as of yet, few have found the way. However, some innovative companies have managed to overcome this hurdle, with smart partnering emerging as one way to create value for both the business and society simultaneously. Smart partnering focuses on key areas of impact between business and society and develops creative solutions that draw on the complementary capabilities of both to address major challenges that impact each partner. In this article, we build on lessons from smart partnering to provide a practical way forward for leaders to assess the true opportunities of CSR.

Mapping the CSR space

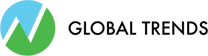

There is no single accepted definition of CSR, which leads to plenty of confusion about what constitutes a CSR activity. We can start to develop a working definition of CSR by thinking about its dual objectives—benefiting business and society—and the range of potential benefits in each case (Exhibit 1).

Many businesses pursue CSR activities that can best be termed pet projects, as they reflect the personal interests of individual senior executives. While these activities may be presented with much noise and fanfare, they usually offer minimal benefits to either business or society. In the middle are efforts that can make both sides feel good, but that generate limited and often one-sided benefits. With philanthropy, for example, corporate donations confer the majority of benefits on society (with potential but often questionable reputational benefits to the business). Similarly, in what’s best referred to as propaganda, CSR activities are focused primarily on building a company’s reputation with little real benefit to society. Some cynics suggest that this form of CSR is at best a form of advertising—and potentially dangerous if it exposes a gap between the company’s words and actions.

Exhibit 1

Corporate Social Responsibility: The Landscape

None of these approaches realize the opportunities for significant shared value creation that have been achieved through smart partnering. In such ventures, the focus of the business moves beyond avoiding risks or enhancing reputation and toward improving its core value creation ability by addressing major strategic issues or challenges. For society, the focus shifts from maintaining minimum standards or seeking funding to improving employment, the overall quality of life, and living standards. The key is for each party to tap into the resources and expertise of the other, finding creative solutions to critical social and businesses challenges.

So how does this work? The examples in the two accompanying sidebars (see “Addressing rural distribution challenges in India” and “Ensuring sustainable supplies of critical raw materials”) illustrate smart partnering initiatives at Unilever. Both address long-term strategic challenges facing the company and build creative partnerships that accrue significant benefits to both sides.

Initial questions for any leader should be “Where have you focused CSR activities in the past?” and, importantly, “Where should you focus them for the future?” All organizations have to balance limited resources and effort, so the challenge is how best to deploy yours to maximize the benefits to your business (and your shareholders and stakeholders), as well as to society. Start by mapping your current portfolio of CSR initiatives on the framework shown in Exhibit 1 and ask: What are the objectives of our current initiatives? What benefits are being created and who realizes these? Which of these initiatives helps us to address our key strategic challenges and opportunities?

Focusing CSR choices: Guiding principles

Companies are likely to have activities scattered across the map, but that’s not where they have to stay—nor is it how the benefits of CSR are maximized. Many companies start with pet projects, philanthropy, or propaganda because these activities are quick and easy to decide on and implement. The question is how to move toward CSR strategies that focus on truly cocreating value for the business and society. The accompanying examples suggest three principles for moving toward this goal.

1. Concentrate your CSR efforts. Management time and resources are limited, so the greatest opportunities will come from areas where the business significantly interacts with, and thus, can have the greatest impact on, society. These areas are where the business can not only gain a deeper understanding of the mutual dependencies but also in which the highest potential for mutual benefit exists.

2. Build a deep understanding of the benefits. Even after selecting your chosen areas of opportunity, finding the potential for mutual value creation is not always straightforward. The key is finding symmetry between the two sides and being open enough to understand issues both from a business and a societal perspective.

3. Find the right partners. These will be those that benefit from your core business activities and capabilities—and that you can benefit from in turn. Partnering is tough, but when both sides see win-win potential there is greater motivation to realize the substantial benefits. Relationships—particularly long-term ones, that are built on a realistic understanding of the true strengths on both sides—have a greater opportunity of being successful and sustainable.

Appling these principles to choosing the appropriate CSR opportunities prompts additional questions—namely: What are the one or two critical areas in our business where we interface with and have an impact on society and where significant opportunities exist for both sides if we can creatively adjust the relationship? What are the core long-term needs for us and for society that can be addressed as a result? What resources or capabilities do we need and what do we have to offer in realizing the opportunities?

Building the business case

In smart partnering, mutual benefit is not only a reasonable objective, it is also required to ensure long-term success. But this commitment must be grounded in value-creation potential, just like any other strategic initiative. Each is an investment that should be evaluated with the same rigor in prioritization, planning, resourcing, and monitoring.

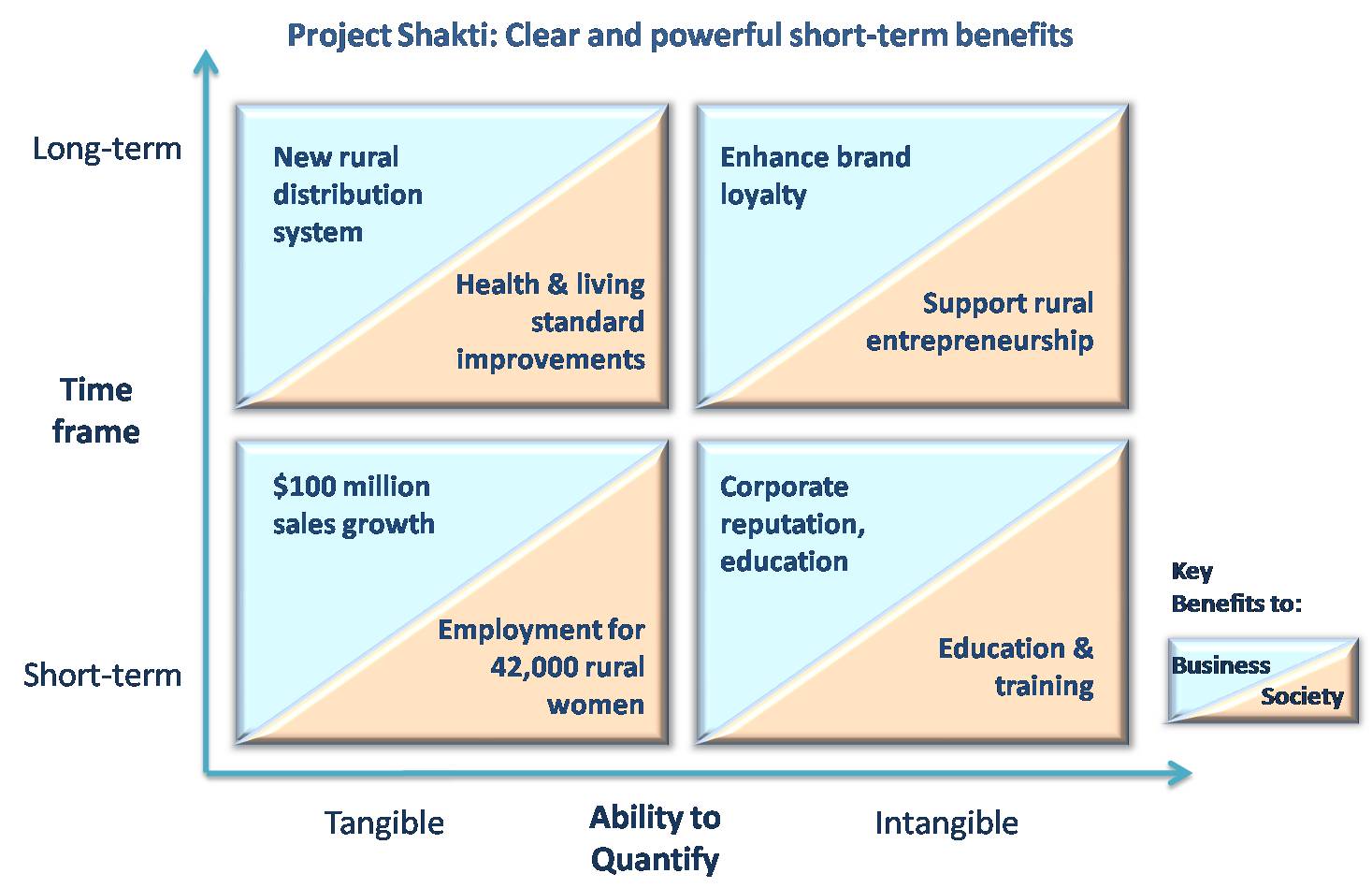

Now you need to define the array of potential benefits for both the business and for society. This will not always be easy but a clear business case and story is important if you are to get the company, its shareholders, and its stakeholders on board. You can assess the benefits across the following three dimensions:

- Time frame. Be clear on both the short-term immediate objectives and the long-term benefits. In smart partnering, the time frame is important as initiatives can be complex and take time to realize their full potential.

- Nature of benefits. Some benefits will be tangible, such as revenue from gaining access to a new market. Others will be equally significant, but intangible, such as developing a new capability or enhancing employee morale.

- Benefit split. Be clear about how benefits are to be shared between the business and society. If they are one-sided, be careful you are not moving into the philanthropy or propaganda arena. Remember that if the aim is to create more value by partnering than you could do apart, then benefits must be shared appropriately.

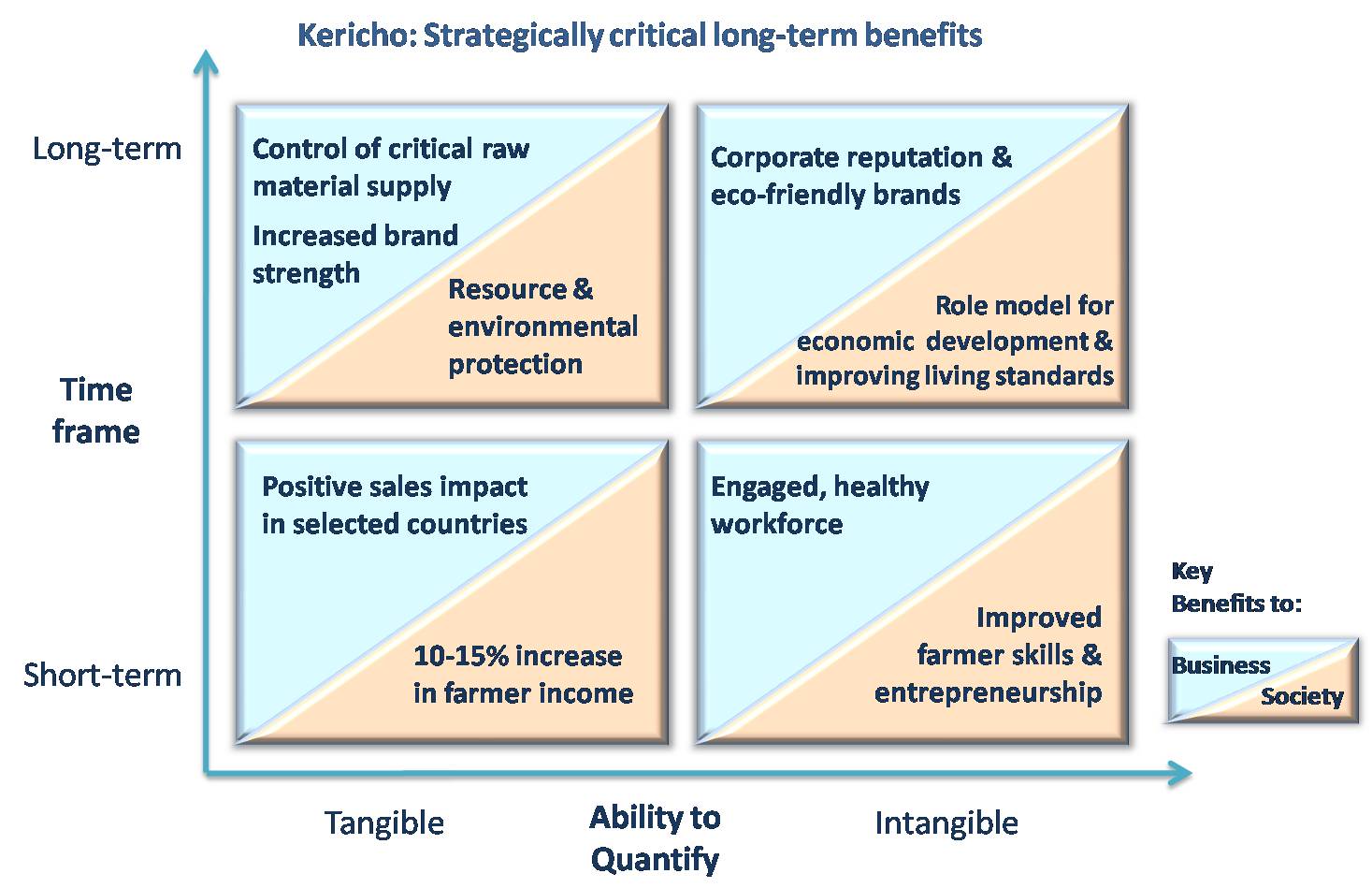

Exhibit 2 outlines two contrasting benefit arrays for the Unilever examples discussed in the accompanying sidebars. With Project Shakti, the short-term tangible benefits are extremely clear and powerful, while in the case of Kericho the long-term intangible benefits are strategically critical for both the business and the communities in which it operates. Remember that it is not essential to have benefits in every section of the matrix. However, if you are struggling on any of the dimensions—for example, there are no long-term or tangible benefits or if most of the benefits are one-sided—go back and ask if this is a real partnering opportunity where significant mutual value creation is possible.

As you develop a clear benefits array, business case and story to communicate to all stakeholders, ask: Do we have a clear understanding of the entire benefits array and associated business case, on which we can focus, assess, and manage the potential CSR activity? Does the activity focus on fundamental value creation opportunities where we can really partner with society to realize simultaneous benefits? Are the opportunities significant, scalable, and supportive of our overall strategic priorities?

Exhibit 2

Plotting the Benefits

Implementing CSR with consistency and determination

Partnering, as we all know, can be challenging. It requires planning and hard work to assess potential mutual benefits, establish trust, and build and manage the activities, internally as well as externally. But is it worth it? Companies at the forefront of such partnering suggest the answer is a resounding yes, but an additional two principles need to be followed to ensure success:

—Go in with a long-term commitment. Having a positive impact on societal issues such as living standards is not a “quick fix” project. Leaders who want to partner therefore need to have a long-term mind-set, backed up by solid promises and measurable commitments and actions. Your initiative must demonstrate added value to both shareholders and stakeholders over time.

—Engage the entire workforce and lead by example. Your workforce can be one of your greatest assets and beneficiaries when it comes to CSR activities. Employees are increasingly choosing to work for organizations whose values resonate with their own. Attracting and retaining talent will be a growing challenge in the future, so activities that build on core values and inspire employees are key. Unilever, along with other leaders in smart partnering, actively engages its employees in such initiatives, seeing improved motivation, loyalty, and ability to attract and retain talent as a result. Engaging the workforce starts at the top. Leaders must be prepared to make a personal commitment if the activities are to realize their full potential.

This is the tough bit of the process: taking action, rather than speaking about it, and keeping up the momentum even when targets are far in the future. As you plan the implementation of your chosen initiatives and follow through, ask: Can we build the commitment we need across the organization to make this happen—and are we as leaders willing to lead by example? Have we planned effectively to ensure implementation is successful, with resources, milestones, measurement, and accountability? How can we manage the initiative, focusing on the total array of benefits sought, not just the short-term financials?

What’s a leader to do?

When it comes to CSR, there are no easy answers on what to do or how to do it. A company’s interactions and interdependencies with society are many and complex. However, it is clear that approaching CSR as a feel-good or quick-fix exercise runs the risk of missing huge opportunities for both the business and society. Taking a step-by-step approach and following the principles outlined here offers leaders a way to identify and drive mutual value creation. But it will demand a shift in mind-set: the smart partnering view is that CSR is about doing good business and creatively addressing significant issues facing business and society, not simply feeling good. And smart partnering is not for the meek of heart. It requires greater focus, work, and long-term commitment than do many standard CSR pet projects, philanthropic activities, and propaganda campaigns, but the rewards are potentially much greater for both sides.

About the Authors:

Tracey Keys is Director of Strategy Dynamics Global Limited and also works with the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), in Lausanne, Switzerland, where Thomas Malnight is a professor of strategy and general management. Kees van der Graaf is Executive-in-Residence at IMD, following his retirement from the board of Unilever, where he was also president of the European business.

This article was first published in The McKinsey Quarterly online, www.mckinseyquarterly.com in December 2009.

©Tracey Keys, Thomas W. Malnight and Kees van der Graaf. All rights reserved. Not to be used or reproduced without permission.

|

Sidebar 1: Ensuring sustainable suplies of critical raw materials Unilever’s Lipton unit is the world’s largest buyer of tea. In 1999, Unilever Tea Kenya started a pilot program in Kericho, in southwestern Kenya, to apply company sustainability principles to the production of tea. The initiative focused on improving productivity, sustainability, and environmental management, as well as energy and habitat conservation. For Unilever, growing pressure on natural resources means that securing high-quality supplies of critical raw materials in the long term is of paramount strategic importance. The Kericho initiative had a direct impact on the company’s ability to control the supply of tea not just today but also into the future, while simultaneously enhancing Unilever’s corporate reputation with both consumers and employees. Company leadership felt that higher short-term costs were far outweighed by the long-term strategic edge Unilever gained for its raw materials supplies and brands. As a signal of its commitment, in 2008 Unilever expanded the scope of its sustainable agriculture program, pursuing certification from the Rainforest Alliance for all Lipton tea farms by 2015. For society, the initiative increased farmer revenue through a 10 to 15 percent premium paid above market prices. Additionally, it focused on topics of significant concern for governments and farmers alike, including improving farmer skills, environmental protection, and sustainable production methods (such as developing a self-sufficient ecosystem), as well as enhancing local associated jobs. All these factors contributed to strengthened rural income, skills, and living standards.

Sidebar 2: Addressing rural distribution challenges in India Over 70 percent of India’s population resides in rural villages, scattered over large geographic areas with very low per capita consumption rates. For multinationals, the cost of reaching and serving these rural markets is significant, as typical urban distribution approaches do not work. Hindustan Unilever Limited’s Project Shakti overcame these challenges by actively understanding critical societal and organizational needs. HUL partnered with three self-help groups whose members were appointed as Shakti entrepreneurs in chosen villages. These entrepreneurs were women, as a key aim for the partnership was to help the rural female population develop independence and self-esteem. The entrepreneurs received extensive training and borrowed money from their self-help groups to purchase HUL products, which they then sold in their villages. By 2008, Shakti provided employment for 42,000 women entrepreneurs covering nearly 130,000 villages and 3 million households every month. In the same year, HUL sales through the project approached $100 million. Dalip Sehgal, then executive director of New Ventures at HUL, noted: “Shakti is a quintessential win-win initiative and overcame challenges on a number of fronts. It is a sales and distribution initiative that delivers growth, a communication initiative that builds brands, a micro-enterprise initiative that creates livelihoods, a social initiative that improves the standard of life, and catalyzes affluence in rural India. What makes Shakti uniquely scalable and sustainable is the fact that it contributes not only to HUL but also to the community it is a part of.”1 [1] V. Kasturi Rangan and Rohithari Rajan, “Unilever in India: Hindustan Lever’s Project Shakti,” Harvard Business School case 9-505-056, June 27, 2007. |