My time in Asia over the past decade has been dotted with epidemics and epidemic scares. These have mainly involved different varieties of the ‘flu, but also other less deadly but still quite bothersome ailments, such as dengue fever. Having just experienced the latter myself – although admittedly a rather mild bout according those in the know – your occasional correspondent is now back in business and eager to share some thoughts on the topic!

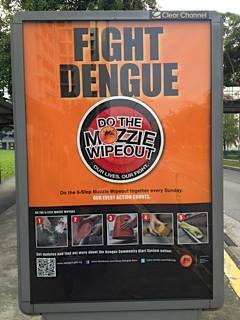

Here in Singapore, we are currently experiencing the worst year for cases of dengue fever since 2005. The city state’s approach to risk management includes a commitment to transparency and public information, and a great deal of public involvement. The government has a dedicated website to inform the public about outbreaks and prevention measures (where we have learned that one major cluster literally surrounds our children’s school…). With newly infected cases exceeding 500 per week at the end of April, the national dengue campaign “Do the Mozzie Wipeout” was launched, calling on everyone in the community to do their bit to prevent the spread of the disease. Volunteers have even been mobilized to pick up rubbish that may hide breeding grounds for the dengue-carrying Aedes mosquitoes. Scientific studies over the past decade indicate that climate change and rising temperatures are contributing factors to an increased incidence of dengue. Although the jury is still out on the exact causes of the current surge in Singaporean infections, the public health response of choice here is transparency and public information. And this healthy trend seems to be spreading.

A milestone in epidemic risk management in Asia was the SARS-outbreak, which killed over 700 of the 8000 people infected in Southern China and Hong Kong in 2002-2003, but provided valuable lessons for many governments. These were sorely needed in many cases. My personal experience of SARS was short as I happened to be travelling outside Asia at the time. But touching down on Mongolian tarmac after a month abroad, I was not the only one on the plane surprised to see “visitors” boarding before the fasten seatbelt signs were off. They looked quite surreal in haphazard protective gear (bandaging, foam rubber, welding glasses and lab-coats), randomly collecting information allegedly pertinent to the passengers’ potential SARS exposure. An hour passed before we could leave the plane. It was as though authorities were caught off guard and wanted to do everything to show the world that they were not.

So how did other countries deal with SARS? Singapore was criticized by some for its arguably drastic measures in trying to prevent the spread of the disease (including virtual house arrest of infected persons). However, its core strategy focused on transparency and mobilization of senior political leaders, which ultimately instilled public trust in the government’s ability to manage the epidemic. Beijing, on the other hand, was criticized for inaction and lack of transparency. In fact, a Chinese colleague of mine once said that she only learned that SARS existed in China when reading about it in a Thai newspaper while on vacation at the height of the crisis. She was shocked to find that China was, in fact, the epicenter of the pandemic. This was not a coincidence. There was an effective news blackout in China for several months after the initial cases were detected, causing rumors and fear among the population. As so often when it comes to China, observers look for political causes, and there were indeed ample in this case: top politicians were busy preparing for the upcoming party congress, and there was the usual fear of disrupting political stability and constant economic development (upon which the legitimacy of the communist party is based). “Better cover it up and not upset the people,” even though this might mean risking people’s lives, seemed to be the attitude. Another impediment was the inexperience of an authoritarian system in allowing effective communication and reporting from the provinces to the central government on the one hand, and from the central government to the people on the other. Political considerations have certainly overruled public health concerns in China several times over the years, including after SARS, for example the ban on reporting of the melamine in baby-milk scandal during the much coveted 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Despite this, there seems to be general agreement that China has learned something from the SARS crisis. The new strain of bird flu H7N9, initially found in and around Shanghai earlier this year, has now spread southwards to Fujian province and even to Taiwan. The strain is considered by the WHO to have a high mortality rate (20% to date, with a large number of infected persons still sick) and is spreading relatively fast, although there is currently no evidence of human-to-human transmission. What is China’s response: increased transparency! The authorities are seeking advice from other countries on how to deal with the epidemic, and are providing timely and accurate information to the public. The transparency trend is obvious from a quick check on the website of China’s health ministry – there’s an up-to-date account of number of cases and affected provinces. Lesson learned.

So it seems like the trend here is a positive one: the recipe for successful governance of epidemics spells transparency and trust – the former will contribute to the latter. Might these health crises contribute to increased openness of government affairs in other areas, and possibly to political changes down the road? Quite possibly, as evidenced by the Chinese example. Would it be overly optimistic to hope that the new SARS-like virus spreading in Saudi Arabia is the beginning of a new era of more transparent governance there? I hope so, but I am not holding my breath.

Links:

Dengue in Singapore

http://app2.nea.gov.sg/news_detail_2013.aspx?news_sid=20130428511593875826

Dengue and climate change

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc1533051/ http://www.emeraldinsight.com/journals.htm?articleid=1524303&show=pdf

China and SARS

http://www.csmonitor.com/World/2013/0313/Was-SARS-fallout-a-lesson-for-China-in-global-citizenship

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92479/

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1155641/transparency-key-lesson-learned-sars-outbreak-mainland-china

China better at transparency when it comes to pandemics

H7N9 in China

http://www.cnbc.com/id/100697408

http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohwsyjbgs/s3578/201305/0f0c5a697d10406ea99a6ef78b99f947.shtml

http://www.straitstimes.com/breaking-news/singapore/story/moh-releases-statement-h7n9-following-first-reported-case-taiwan-20130

SARS-like virus in Saudi Arabia

http://www.timelinenews.org/world/health-education/item/4041-saudi-victims-of-sars-like-virus-didn-t-travel-doctor.html

About the difference between epidemic and pandemic

http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/148945.php